Now that the elections are over, the fighting has really begun. Washington is waiting anxiously while legislators from both parties and the Obama administration try to decide what to do about the “fiscal cliff.” Going over the cliff would suck more than $600 billion worth of fiscal stimulus out of the economy in 2013 through a combination of tax increases and spending cuts. That would be disastrous for everyone, including, one assumes, the politicians who lead us over the edge. And yet, a peek into the abyss might show our politicians, like nothing else can, exactly why they need to get serious about putting the nation’s finances on firmer ground.

Even a brief dive—a bungee jump, if you will—would be scary indeed. In its latest projection, the Congressional Budget Office predicts that the post-cliff economy would shrink for the first half of the year, at an annualized pace of 1.3 percent. While recovery should come in late summer, growth for the whole year would be a meager half a percentage point. That’s a pretty grim picture given the still-sluggish state of the economy.

And yet, our fiscal situation is so crazy that a few analysts have begun suggesting that maybe, just maybe, going over the fiscal cliff is our best hope. Bruce Bartlett, a former Reagan administration official and latter-day critic of the GOP’s profligate spending during the administration of George W. Bush, recently wrote for The New York Times website about “The Fiscal Cliff Opportunity.” Peter Schiff, the head of Euro Pacific Capital, has been even blunter. The biggest risk is not that “we go over this phony fiscal cliff,” Schiff said in a recent interview. “It’s [that] the government cancels the spending cuts, cancels the tax hikes,… [and] instead we end up going over the real fiscal cliff further down the road.”

“In fact,” he added, “the real fiscal cliff comes when our creditors want their money back and we don’t have it.”

He may be right. The amount of debt held by the public has increased from $4.9 trillion in the beginning of 2007 to $11.5 trillion today—from 36 percent of GDP to 75 percent of GDP. The last time our debt-to-GDP ratio was this high, Harry Truman was president.

While of course a lot of that was loaded on during the financial crisis, our debt is still increasing by about $2 billion a day. With interest rates so low, that much debt is not currently a problem. But if interest rates increased just 2 percent, we’d have to pay an additional $230 billion every year in interest costs. If they go up to 5 percent, which would be closer to their historical norm, we’ll be on the hook for half a trillion dollars a year—on top of our ballooning bills for baby-boomer retirements.

Creditors are fully aware of this dismal math; they’re lending to us mostly because other countries are even worse. But how long will we be able to keep borrowing $1 trillion a year?

Of course, Barack Obama’s most recent budget predicts that the deficit will fall to 5.5 percent in 2013. Coincidentally, that’s almost exactly what his 2010 budget predicted the deficit would be … in 2011. We seem to be better at predicting deficit reduction than achieving it.

That’s not catastrophic right now. But with the economy still lackluster, there’s a danger that we will never find the right time for deficit reduction.

Virtually all economists agree about what we need to do: keep the tax cuts for the short term, and put off the automatic spending reductions, while also putting together a sensible, sustainable package of long-term reforms. Most also roughly agree on what the reforms should look like: structural entitlement reform, including higher retirement ages; some sort of cap on health-care-spending growth; and radical tax reform that actually cuts marginal tax rates but also eliminates most deductions, so that we actually collect more revenue from most taxpayers.

“The essence of this problem is that there is no No. 1 thing we need to do,” says Alice Rivlin, the first head of the Congressional Budget Office and co-chair of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Debt Reduction Task Force. “We need more revenue and a better tax code. We must slow the rate of growth of the entitlements.”

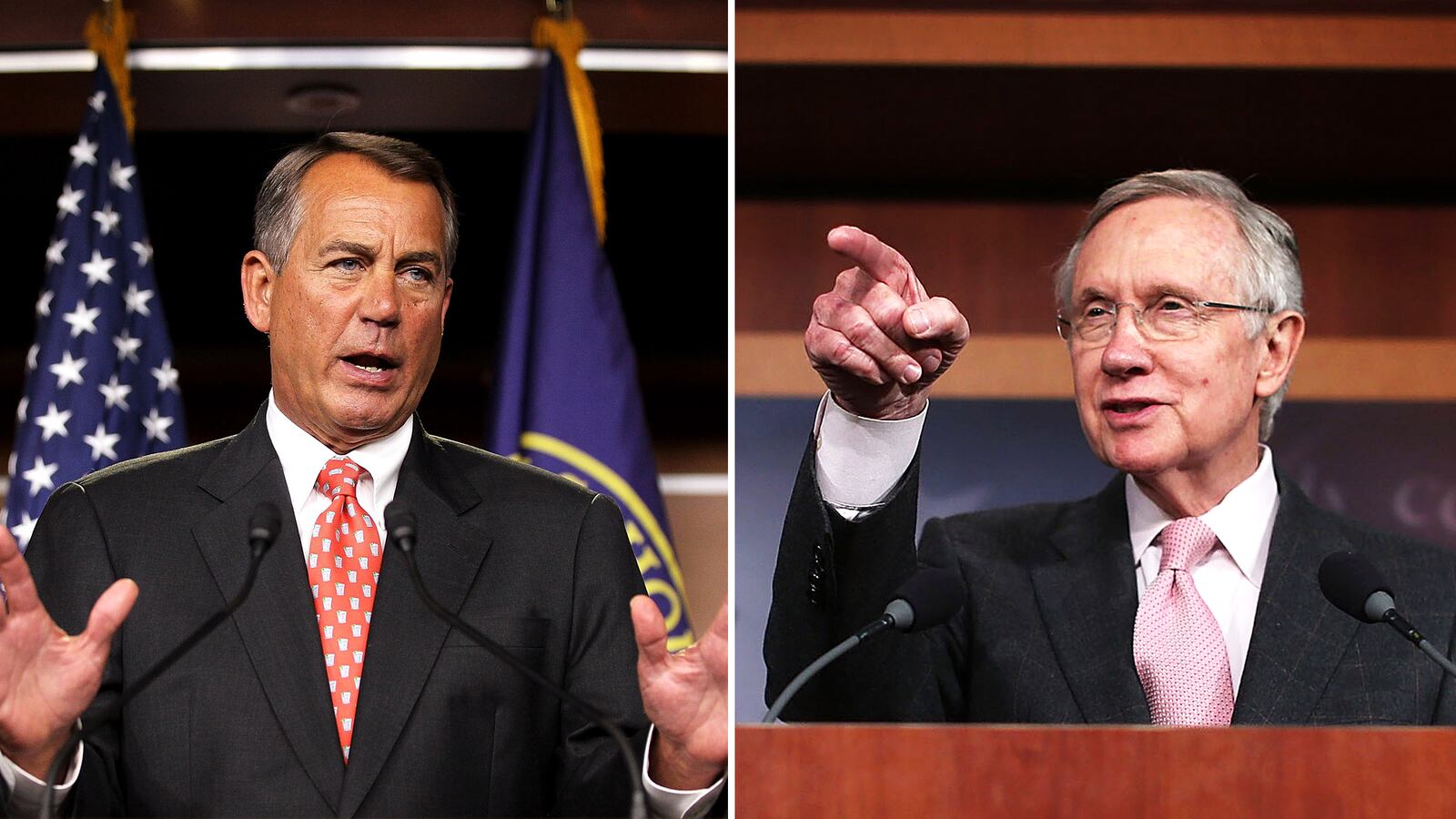

The problem, predictably, is Washington. With interest rates at record lows, politicians seem to be willing to borrow forever rather than make serious, long-term concessions on the issues near and dear to their hearts. Democrats are fiercely divided over the issue of retirement age changes and other entitlement reforms; the only thing they agree on is higher taxes for the rich. And while the GOP leadership has made some noises about raising revenue, the firebrands brought to Congress by the rise of the Tea Party seem inalterably united against it.

Even after Standard and Poor’s downgraded the U.S. credit rating in response to Republican brinksmanship over raising the debt ceiling, many in the GOP continued to belligerently insist that it wasn’t their fault. “This device of saying ‘We won’t fund the government’ is new, and it’s working,” says Ken Rogoff, a Harvard professor who used to be the chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. This is in part because it plays well with voters: “The average voter doesn’t understand that you can’t stop this freight train running 120 miles an hour on a dime.”

That braking time is why we need to get started sooner rather than later. We can afford to keep borrowing for a while … but not so long that we can delay structural reforms indefinitely. And if we don’t get a deal together soon, the political calendar will make it hard to get one together in the foreseeable future. “If you don’t do it by August 2013, you can’t do it in 2014,” former presidential adviser Doug Holtz-Eakin told the Peterson Institute’s conference on the fiscal cliff a few weeks ago. “That’s an election year. So now you can’t do it until 2017.”

“Greece, Spain—they all saw this problem coming and said, ‘we don’t have to do something now,” says Rivlin, echoing the point.

But Washington doesn’t seem particularly close to a deal. Even as some Republicans are starting to say, grudgingly, “Well, we lost,” Democrats seem to think this means they should take a tougher stance. In a speech at the National Press Club, Chuck Schumer, the third-ranking Democrat in the Senate, urged his party not to make compromise with Republicans on higher rates. “The old style of tax reform is obsolete in a 2012 world,” he told the audience, later declaring that it would be “a huge mistake to take the dollars we gain from closing loopholes and put them into reducing rates for the highest income brackets, rather than into reducing the deficit.” Sen. Dick Durbin has said that entitlement reform should be off the table for now—maybe later, but only after the GOP caves on taxes as a gesture of goodwill. Sen. Patty Murray, a senior member of the Budget Committee, says that she’d rather go over the cliff than see the Bush tax rates extended for top earners. The administration seems to agree: even as Republicans talked about maybe raising some revenue by limiting deductions, the administration insisted that tax rates on high earners absolutely must rise.

“What’s disturbing to me is that Democrats are saying, ‘maybe we can gain if we go off the cliff,’” Sen. Alan Simpson told the summit. Simpson, along with Erskine Bowles, chaired the president’s 2010 bipartisan debt commission—the one that ended without enough votes to pass its own recommendations. “Republicans are saying ‘maybe we can gain.’”

Bowles agreed. “We have to get serious. We have about $2.3 trillion in revenue coming into the country. We’re spending $3.6 trillion. We have to grow up. It won’t be long before all we can do is take care of a few old coots like me and Alan, and nothing else.”

Nonetheless, at the summit, Simpson put the chances that both parties would go over the cliff rather than compromise at 30 percent. In a Nov. 28 interview with the Christian Science Monitor, Bowles raised that to 66 percent.

Our political parties are playing a game of chicken with the nation’s long-term fiscal and economic well-being—with each hoping the other side flinches first, forcing it to pay the bulk of the political costs of any reform.

The way to win a game of chicken, game theorists will tell you, is to rip off your own steering wheel and throw it out the window, so that your opponent knows you can’t turn the car. Unfortunately, the game theorists don’t tell you what you should do if you look out your window and see the other guy doing the same thing.

Unless something changes, we’re headed toward one of two uncomfortable places. Either we veer over the fiscal cliff and the economy crashes—or we keep going down the road we’ve been taking for more than a decade, delaying hard choices while assuring voters that no really hard choices need to be made. That road probably ends in an even nastier smashup. “Going over the fiscal cliff puts us into a horrible, self-created, and totally unnecessary recession, but then we come out of it,” says Marc Goldwein, senior policy director of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. On the other hand, “if we keep racking up the debt, we don’t know when the crisis will hit. But historically, it will be fast, and we’ll have to go over a fiscal cliff anyway.” Only by then, the debt will be even larger, and we’ll have even less time to do anything about it.

So maybe the first cliff—the one coming in January—is the lesser of two evils. It just might achieve what white papers and impassioned pleas have so far failed to do: scare some sense into our legislators. Now all we have to do is hope that they pull out of the dive before we all hit bottom.