As the Supreme Court considers potentially landmark gay-marriage cases this week, there’s one previous Supreme Court decision that won’t be cited by any of the advocates but is sure to be on the minds of the justices. It’s the case of Bowers v. Hardwick, and it was the first major Supreme Court ruling on gay rights. Decided in 1986, Bowers held that gay people had no right to intimate relationships with people of the same sex. And while Bowers has since been overturned and is no longer binding law, it may nonetheless influence the court’s decision in the marriage cases—especially the vote of the likely “swing” justice, Anthony Kennedy.

The Bowers case began when 29-year-old Michael Hardwick missed a court appearance for a petty offense of public drinking. The court issued an arrest warrant for Hardwick, and when police went to his home, they found him in his bedroom having oral sex with another man. Hardwick was arrested and charged with violating Georgia’s law that made sodomy a crime. Many states had similar laws against sodomy—oral or anal sex—but they were rarely enforced against consenting adults, whether gay or straight. Indeed, the prosecutor in Hardwick’s case dismissed the charges against him. Hardwick, however, backed by gay-rights activists seeking to strike down sodomy bans, filed suit claiming the law violated his right to privacy.

His case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, yet the timing was less than ideal. The court was mired in a bitter public controversy over its most recent decision to expand privacy rights: the court’s 1973 decision on women’s right to choose abortion, Roe v. Wade. And the mid-1980s was the height of the AIDS epidemic, which many people mistakenly saw as a gay disease—one that was spread through sodomy. Hardwick was asking the justices to declare that he had a constitutional right to engage in the very act that seemed to be devastating the gay community.

Nonetheless when the justices first voted on Hardwick’s case, there were five votes to throw out the sodomy law. One of those votes belonged to Justice Lewis Powell, a well-heeled, patrician justice from Virginia appointed by Richard Nixon. Powell, who had once headed up the American Bar Association, unexpectedly changed his vote and decided to side with the four justices who thought sodomy bans were constitutionally permissible. That made the vote 5-4 to uphold Georgia’s laws. Powell explained to one of his law clerks at the time, “I don’t believe I’ve ever met a homosexual.”

The clerk to whom he was speaking was himself a closeted gay man.

The majority’s decision in Bowers was written by Justice Byron White. Nicknamed “Whizzer” in college, where he was a standout football player—he was a finalist for the 1937 Heisman Trophy and then the No. 1 draft pick of Pittsburgh’s professional football team—White was appointed to the Supreme Court by President John F. Kennedy. While we often hear about justices appointed by Republicans who turn out to be more liberal than expected, White was a Democratic nominee who turned out to be very conservative. He voted to narrowly read the Constitution’s protections against racial discrimination and consistently criticized the court’s privacy rulings, like Roe.

White’s opinion for the court in Bowers not only rejected Michael Hardwick’s claim that same-sex intimacy was a constitutionally protected form of privacy, it was unusually harsh in doing so. The gay man’s claim, White said, was “at best, facetious.” Sodomy had been a criminal offense at the time of the framing, according to White, and granting this conduct constitutional protection would necessarily lead the court down a slippery slope that might require striking down laws barring “adultery, incest, and other sexual crimes.” “We are unwilling to start down that road.”

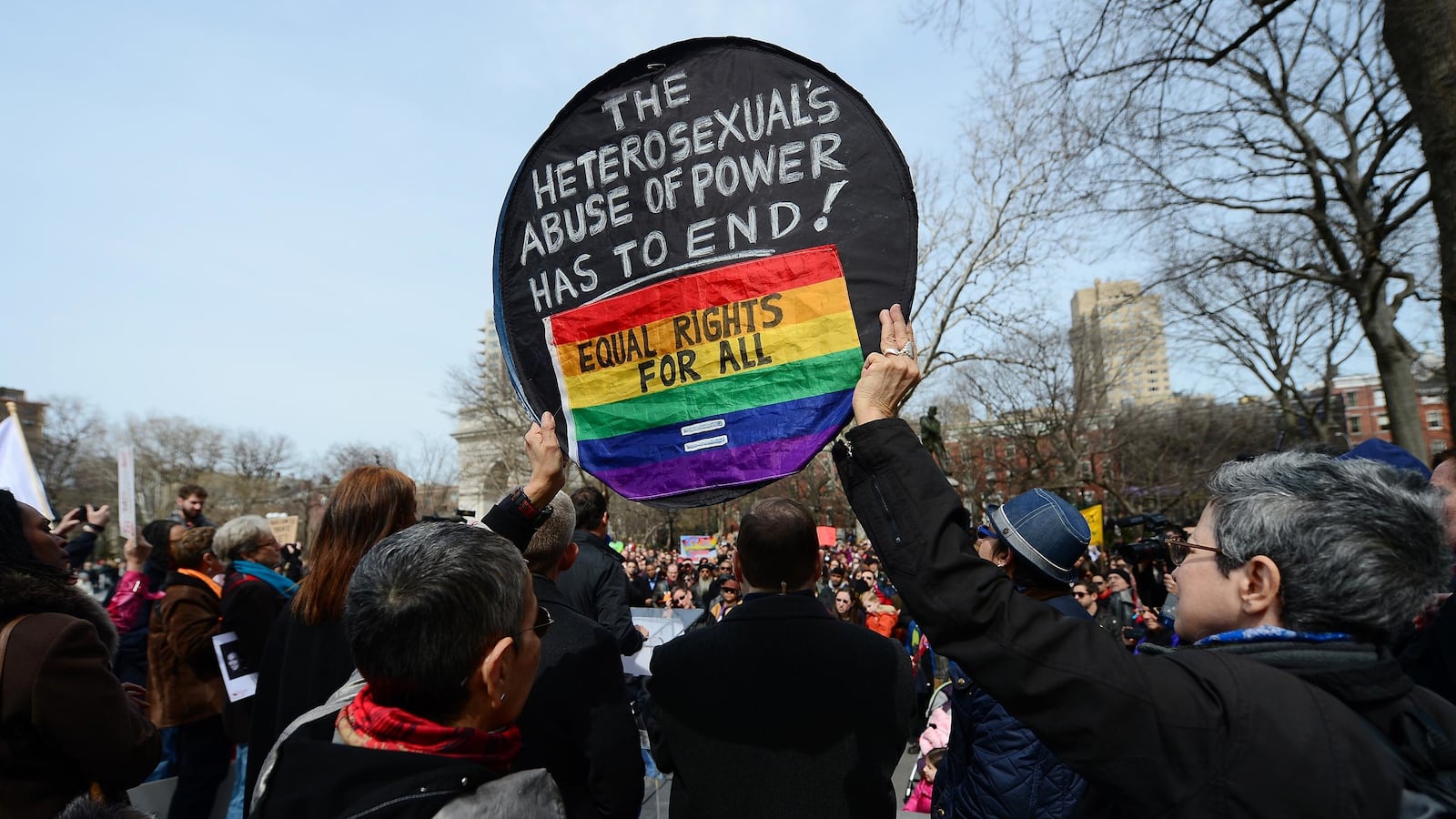

The Bowers decision triggered an avalanche of criticism. Scholars criticized the court’s history, noting that sodomy bans, despite being on the books, were almost never enforced against consenting adults regardless of their sexual orientation. Richard Posner, arguably the most high-profile conservative legal thinker of the time and who was himself appointed to the bench by President Ronald Reagan, condemned the decision for its lack of empathy for and understanding of gay people. The case also galvanized the gay-rights movement, which grew exponentially in its wake.

Justice Powell resigned from the court the next year, replaced by Anthony Kennedy. In 1990, during an appearance at New York University Law School, Powell expressed regret for his vote in the Bowers case. “I think I probably made a mistake in that one,” he frankly admitted. Indeed, the court itself came to regret the decision, which was ultimately overturned in 2003, in a case called Lawrence v. Texas. That decision, which declared sodomy laws an unconstitutional violation of the right of privacy, was written by Justice Kennedy.

In the marriage cases to be heard this week, Justice Kennedy will once again be at the center of the controversy. There are likely four votes to strike down discriminatory marriage laws—Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan—and three seemingly certain votes to uphold such laws—Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito. Where Chief Justice John Roberts stands remains a mystery, though his long track record of conservative votes in privacy cases doesn’t provide much encouragement for proponents of gay rights.

Kennedy is clearly a justice who considers how his legacy will be shaped by his votes. In 1992, when the Supreme Court was asked to overturn Roe in a case called Planned Parenthood v. Casey, Justice Kennedy originally sided with the conservatives to reverse the controversial privacy decision. Like Justice Powell in Bowers, Justice Kennedy then changed his vote. He went to see Justice Harry Blackmun, the author of Roe, and explained that he was concerned about how history would judge Kennedy’s decision to end constitutional protections for women’s right to choose.

Like many people, Justice Kennedy may believe that the public tide against marriage discrimination is growing and that gay marriage is inevitable. History is not likely to be kind to those justices who vote to continue relegating LGBT people to second-class citizenship. As the swing justice ponders how to rule in the gay-marriage cases, Justice Powell’s well-known regret over Bowers, and the widespread recognition that Bowers was wrongly decided, will almost certainly weigh on his mind.

Bowers may no longer be good law and will undoubtedly remain unmentioned in this week’s oral arguments. Yet it could be the most important precedent of all.