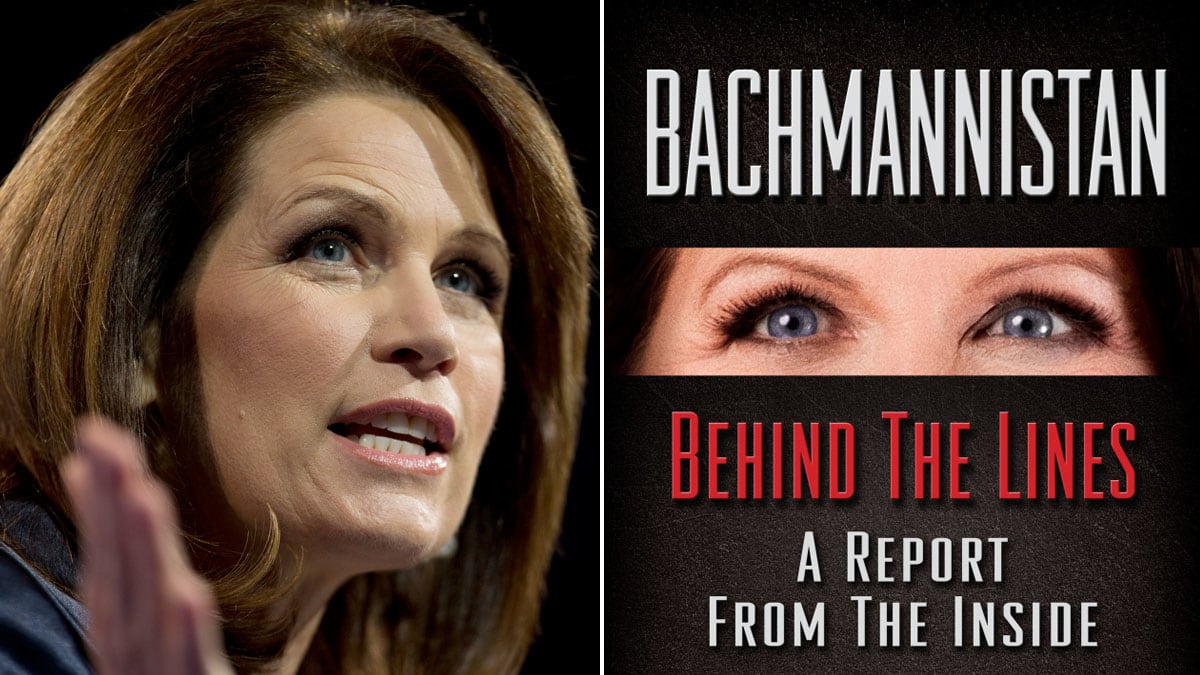

Why is the 2012 presidential campaign of Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-MN) under investigation? In a new e-book, Bachmannistan, Peter Waldron, a longtime evangelical activist who worked on Bachmann’s campaign as a national field coordinator, details the campaign’s implosion and how he says it broke trust with those across the country who volunteered for, donated to, and supported the four-term congresswoman.

In a phone interview with The Daily Beast, Waldron said Bachmann sought to quash the publication of his book, which was published online Monday. That effort, he said, included having her attorney, Bill McGinley of the K Street law firm Patton Boggs, discourage Waldron from publishing. Waldron also said he acquiesced to requests from James Pollack, a top Bachmann aide, not to publish the book before Bachmann’s reelection to Congress in 2012, lest a potential loss deprive Capitol Hill of a voice for “Christians and patriots.” Once Bachmann won and her presidential campaign staff received the back pay they had been owed since 2011, Waldron said, he uploaded his e-book.

In Bachmannistan, Waldron attempts to trace how Bachmann’s campaign went off the rails after she won the Ames Straw Poll in August 2011 and became the frontrunner in the Iowa caucuses. The campaign was defined by poor judgment, he said. Every time Bachmann had “the opportunity to make the right decision, the campaign made the wrong decision,” he told The Daily Beast. But he said those decisions weren’t the result just of strategic errors but of deliberate malevolence.

Waldron pointed a finger at Keith Nahigian, who eventually became Bachmann’s campaign manager. Nahigian won an internal fight within the campaign, Waldron said, over whether the Minnesota congresswoman should emulate Rick Santorum’s approach and focus on Iowa or visit Florida, South Carolina, and New Hampshire in an attempt to “look presidential.” According to Waldron, Nahigian, who was doing advance for the campaign, benefited directly from the latter course of action: “He had a vested interest in more travel, more buses, more hotels.” Nahigian could arrange these trips, bill them to the campaign, and then “sign and approve his own invoices,” Waldron said.

Bachmann’s first campaign manager, Ed Rollins, quit over the strategic decision to abandon Iowa, marking the beginning of the decline of Bachmann’s political fortunes. “Santorum put on a pair of blue jeans, sweater vest and drove his pickup truck to every county and small town in Iowa, and he’s from Pennsylvania. [Bachmann] is from Waterloo, Iowa, and she chose the other road,” Waldron said mournfully.

Yet those apparent miscues paled in comparison with the hiring of Iowa state Sen. Kent Sorenson as the campaign’s state chairman, said Waldron, despite state ethics rules against presidential campaigns hiring members of the state legislature.

Sorenson said he could offer, according to Waldron, “an extensive grassroots network with a substantial number of leaders [that could] ... provide momentum through the straw poll and into the caucus,” but that proved to be an exaggeration, he said. Meanwhile, the campaign was paying Sorenson more than $100,000 for his endorsement, Waldron said. While Sorenson seemed like a natural fit for Bachmann at the time, Waldron described him as the “darling of Iowa conservatives, feared by the left and not trusted by RINOs.” The negotiations over Sorenson’s endorsement, Waldron said, focused on how to pay him without having to report to the Federal Election Commission. “A wise campaign would have walked away,” Waldron said. Three days before the caucuses, Sorenson jumped ship and endorsed Ron Paul. Bachmann finished sixth and dropped out of the race the next day.

Sorenson also allegedly landed the Bachmann campaign in hot water by obtaining the email list of an organization of conservative parents who homeschooled their children. An Iowa campaign staffer alleged in lawsuit against the Bachmann campaign that Sorenson stole the list from her personal computer. The suit was settled out of court in late June.

In a statement, James Pollack dismissed Waldron as a “former staffer with an ax to grind.” For his part, Waldron said Bachmannistan isn’t much of a tell-all, as he was repeating what he told law-enforcement agencies investigating Bachmann’s presidential bid over the past year and a half. Waldron said he wanted to share those statements with other Americans who had supported Bachmann. The book is for “the millions of people that donated $15 to $25 to her campaign and want to know what happened to their Michele,” he said. Bachmann announced in late May that she will not seek reelection to Congress.

“I hope they remain in the process, get involved and registered,” he said. “I’m very concerned that her sudden, abrupt retirement will leave a vacuum. We need to find good people who are ethical and lead with integrity. I believe that candidate is there. I am just concerned that the Michele Bachmann experience will alienate them.”