When Caroline Krass steps up to the table later this afternoon for her Senate confirmation as CIA general counsel, most of the tension will center on events that took place more than a decade ago in which she had little or no involvement. And some of the toughest questioning will come from Democrats on the panel who have put the White House on notice that there is far more at stake here than who will be the top lawyer at the nation’s premiere spying organization. That is because the Krass nomination is serving as a proxy battle for one of the most intense and enduring wars between the Senate Intelligence Committee and the CIA in recent memory: the fate of the committee’s massive and, according to sources familiar with it, brutally critical, report on the agency’s harsh interrogation program.

Like everything relating to what the CIA calls enhanced interrogation and critics call torture, the fight over the report has been suffused with acrimony and mutual distrust. For Senator Diane Feinstein, the committee’s chairman, as well as Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR.) and Mark Udall (D-Co.), the two members of the panel who have made the probe their crusade, the report represents a reckoning that is long overdue. But more than that, for them the 6,000-page report represents the authoritative historical record of one of the most divisive and painful chapters in the country’s national security history. Its public disclosure offers an opportunity to finally put one of the CIA’s darkest eras behind it by confronting the full facts and acknowledging mistakes that were made.

The CIA doesn’t reject all of the report’s findings, but officials there say much of it reads like a one-sided prosecution brief filled with errors and unfair insinuations. And even though the CIA has long relinquished controversial techniques, they say the report makes little or no attempt to see the true value of a program that many officials at Langley still maintain saved lives, foiled plots, and led to one of the most heralded intelligence coup in decades—the location and killing of Osama Bin Laden.

For months the CIA has pushed aback against the report’s most critical conclusions, while Democrats on the committee have almost entirely stood their ground. Some of the worst clashes took place earlier this year between Feinstein and CIA Director John Brennan, who engaged in a series of tense conversation over the dispute that more than once degenerated into “shouting matches,” according to a well-placed Senate source.

Publicly CIA officials have said the agency plans to learn from the investigation’s findings and implement necessary reforms. But they too are standing their ground in the belief that significant parts of the report they saw earlier this year were inaccurate. Agency officials pushed back hard trying to correct what they saw as factually flawed. The committee has made some corrections to the report based on the CIA’s rebuttal, but they did no alter the major conclusions, according to two sources familiar with the document, which remains classified. The CIA has not seen the latest version of the report.

In a statement, CIA spokesman Dean Boyd said the agency “agreed with a number of the study's findings, but also detailed significant errors in the study.” He also said that “CIA and [Senate] committee staff have had extensive dialogue on this issue and the agency is prepared to work with the committee to determine the best way forward.”

Caught in the middle–but trying to stay on the sidelines–is the White House, which wants to smooth Krass’s nomination without alienating the spies at the CIA. Obama aides have consistently declined to take a position on the report, instead urging the intelligence panel and the agency work together toward consensus.

“We believe that it is important for the committee and the CIA to continue working together to address issues associated with the report—including factual questions,” said National Security Council spokesperson Caitlin Hayden. “When that process between the committee and the CIA is complete, we understand that the committee will vote on its updated document and then pursue declassification of the document, in whole or in part,” Hayden added.

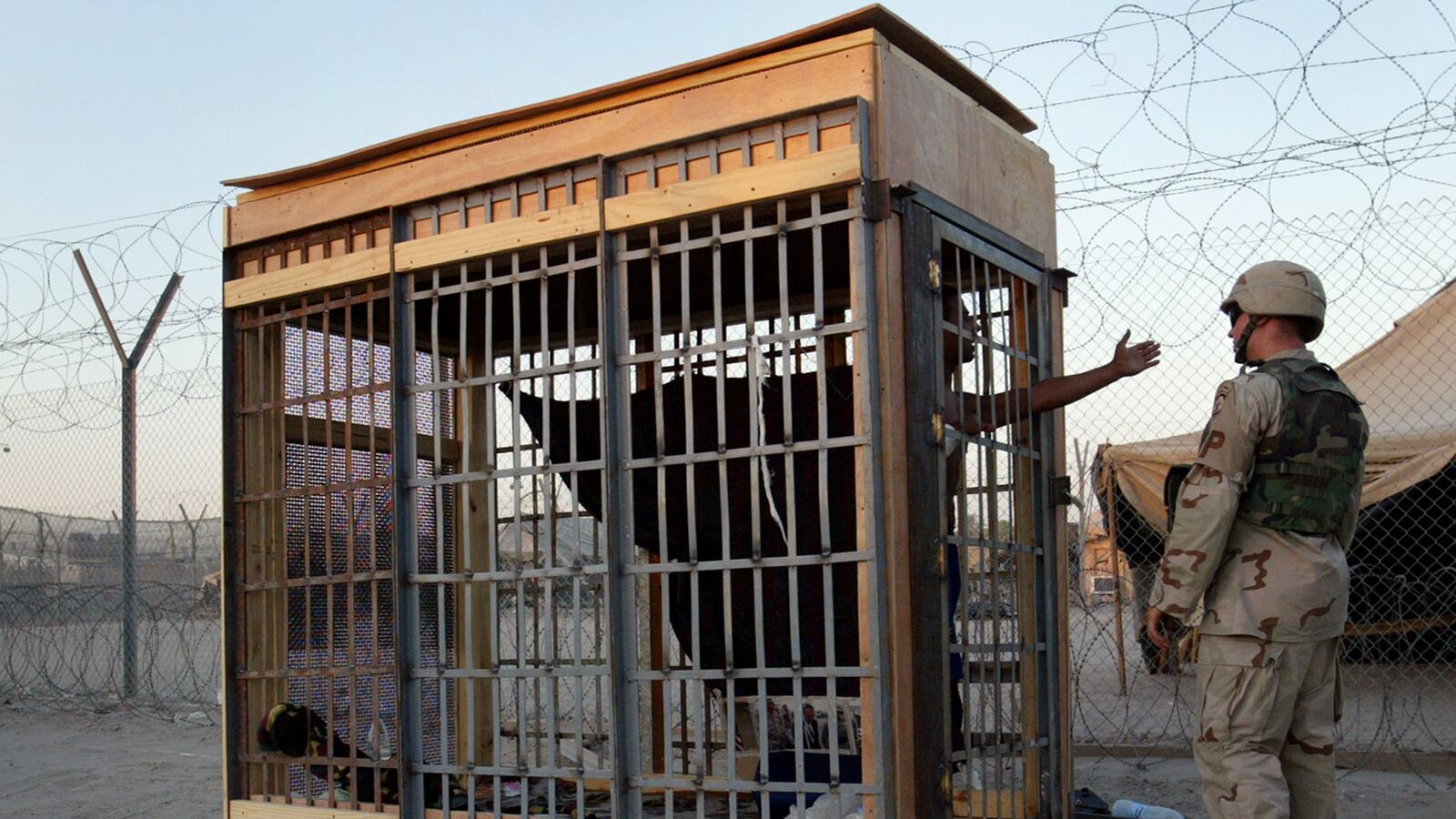

It is not hard to understand why the CIA is dreading the public disclosure of the report. According to those who have read it (or at least its 300-page executive summary), it makes a two-pronged attack on the agency’s credibility. First, it concludes that the CIA’s Enhanced Interrogation Program, which included instances of waterboarding, sleep deprivation, and other forms of harsh questioning techniques, did not yield any significant intelligence that couldn’t have been obtained through traditional, non-coercive measures. Second, and perhaps even more harmful to the CIA’s reputation, the report concludes that senior officials there engaged in a far-reaching, systematic pattern of deception and dishonesty over the efficacy of the program. The report details in granular detail instances in which Senate investigators believe the agency provided misleading or false information to the White House, the Justice Department, and congressional oversight committees.

Among the bill of particulars in the report is faulty information from the CIA that the Justice Department relied on in developing a series of legal opinions reauthorizing the program in 2005. (The original Office of Legal Council [OLC] opinions were withdrawn by Justice in 2004 after lawyers there concluded the legal reasoning behind them was badly flawed.) The 2005 opinions, written by Steven Bradbury, then the head of OLC, rested significantly on assertions from the CIA that the enhanced interrogation program largely prevented attacks on the United States after 9/11, a claim that the committee concluded has not been proven.

In its investigation, the Senate intelligence panel also found that the CIA made inaccurate representations about the efficacy of the program to congressional oversight committees, even over the objections of some agency employees who warned that the assertions may have gone further than the facts warranted.

Determining who was telling the truth about the success of the interrogations program has always been a murky business, dependent on subjective judgments and attempts at proving negatives. One major point of contention between the committee and the CIA is whether the truth of many of the report’s assertions is even knowable. The report contends as a statement of fact that much of the intelligence obtained through coercive treatment could have been obtained using other means. In response, CIA officials have argued that such claims are purely speculative.

It is unclear the extent to which Democrats on the committee will try to draw Krass into the substance of the disagreements. Krass was a career lawyer at the Justice Department Office of Legal Council when all of the department’s legal opinions on the program were written. But sources who worked at OLC at the time tell The Daily Beast that she had no involvement in developing the legal arguments supporting the use of the harsh interrogation techniques.

Still, the confirmation hearing represents one of the only instances in which senators will have any leverage over the administration on the issue. The general counsel job represents one of only three positions at the CIA that are subject to Senate confirmation. Moreover, if Krass is confirmed, she will likely be a crucial player in determining how much of the report can be declassified for public release. Udall and Wyden are expected to use the hearing to try to extract promises from her to make a good faith effort to declassify as much of the report as possible.

Committee sources have indicated that the panel will likely vote to declassify the report (or at least the executive summary) early next year. At that point it will go to a CIA review board, which will make its own judgments about what can be released to the public and what should stay under wraps. That will be followed by negotiations with the intelligence committee, a process that could take months.