This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

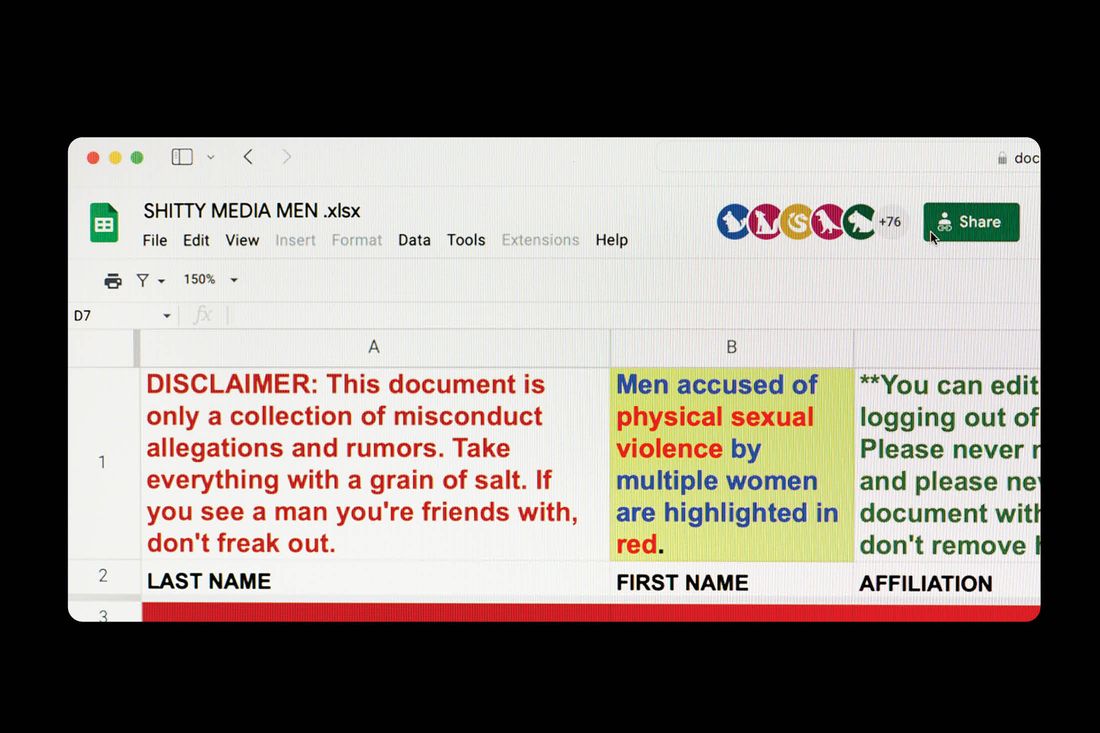

Five years ago, on a Wednesday morning in October, an editor and writer at The New Republic named Moira Donegan sent a handful of women who worked in media a link to a Google spreadsheet titled “Shitty Media Men.” Those women sent it to other women, who sent it to other women. By the end of that night, dozens of users had signed into the document, their anonymous animal avatars crowding the top right corner of the page. They were compiling the names of editors, publishers, and writers who had allegedly harassed or assaulted women. The accusations ranged from “Creepy af in the DM’s” to rape. When the list was taken offline around midnight, more than 70 names had been added. “It was a frenetic moment,” one woman who entered a name told me. A week earlier, the New York Times had published its bombshell investigation into the allegations against Harvey Weinstein, breaking the code of silence that had protected him for decades. A reckoning was at hand, and women who worked on the list felt a sense of hope and vindication. None I spoke with recalled worrying in the heat of the moment that they might one day regret contributing to it. “That first night? It was the most fun thing I’ve ever done in my life,” one woman said.

A note at the top read, “Please never name an accuser, and please never share this document with a man.” The assumption was that women could be trusted. But it was a woman, Doree Shafrir, who broke the story to the public, reporting on it for BuzzFeed in a post that went up soon after midnight. Contributors were furious with her, but they could do nothing to express their anger except block her on Twitter. The list had become an international news story. Some commenters hailed it as an ingenious effort to protect women and as evidence of widespread abuse. Others decried it as irresponsible, malicious, and dangerous.

When Deborah Tuerkheimer, a professor at Northwestern’s Pritzker School of Law, read the coverage, she worried what the future might hold for the accusers. “I realized that — regardless of the truth of the entries — one of the named men might well sue for defamation,” she told me. A year later, on October 10, one of them did. Stephen Elliott was a writer, filmmaker, and the founding editor of The Rumpus. The entry by his name read, in part, “Rape accusations, sexual harassment, coercion” — allegations he has denounced in his lawsuit as “inflammatory false statements.” Elliott doesn’t know who put him on the list. He and Donegan have never met, but he’s suing her for creating the document. He’s also suing 30 Jane Does in an attempt to unmask whoever added him. He’s demanding they publish “a written retraction to each and every person” who received the spreadsheet and is seeking at least $1.5 million in damages. Neither Elliott nor Donegan is paying legal fees. They’re both working with high-profile lawyers who took the case because they believe in the causes their respective clients seem to embody. Elliott’s lawyer, Andrew Miltenberg, is known in the world of defamation law for representing men who have been accused (falsely, he would say) of sexual assault. Donegan’s lawyer, Roberta Kaplan, has a sterling reputation as a defender of women’s rights — or at least she did until last year, when a report claimed she had been involved in an effort to discredit one of then-Governor Cuomo’s alleged sexual-harassment victims, leading her to step down as chair of Time’s Up.

It’s not hard to see Elliott’s lawsuit as part of a broader backlash against the revolutionary spirit of the Me Too movement. His is one of dozens of defamation claims filed by men accused of wrongdoing at the movement’s height. These suits serve as reminders that accusing men of abuse can carry costs for the accusers. This summer, Johnny Depp won more than $10 million in damages against his ex-wife Amber Heard in a case that played out in a swirl of misinformation on YouTube and TikTok.

Defamation cases tend to be hard to win. Plaintiffs carry the burden of proving they didn’t do whatever they were accused of doing. As a result, the cases can drag on for years and accrue huge costs. Most are settled or dismissed. Some lawyers — including Kaplan — initially predicted Elliott’s would be thrown out. But Donegan’s team has twice failed to persuade the judge to dismiss it, and it now appears poised to go to trial.

At stake are two fundamental and conflicting American ideals. From one perspective, the list, and similar documents, violates the spirit of due process and the right to be free from reputation-damaging falsehoods. From another, the lawsuit is an attack on the spirit of free speech and, more specifically, on people’s ability to speak anonymously on the internet, a tradition prized not only by victims of sexual assault but also by political dissidents and aggrieved employees — and, for that matter, trolls on Reddit. The outcome of the case will likely depend on whether the facts that emerge during discovery and in the courtroom can provide answers to these basic questions: Who wrote that Elliott had been accused of rape? What role, if any, did Donegan play in shaping that entry? Can Elliott prove the accusations were false?

Elliott’s own lawyer has acknowledged his client is “a less than perfect plaintiff.” In half a dozen semi-autobiographical books and essays, Elliott has written in frank detail about his sexual experiences as a submissive man in the S&M world, his bouts of heroin addiction, and other aspects of what the general public might consider an unwholesome lifestyle. Although his lawyer didn’t acknowledge this, he has also long had a reputation, as Marisa Siegel, the former editor-in-chief of The Rumpus, put it in an essay, as a man who “has no understanding of boundaries” with women. Yet the “Shitty Media Men” spreadsheet did not just portray him as shitty — it suggested he had committed multiple rapes. His claim includes an unusual argument: that he could not have raped anyone because his sexual habits do not involve penetrating women in any way.

Donegan declined to speak with me, saying she couldn’t comment on an unresolved case. Elliott had no such reservations. “My lawyers didn’t want me to talk to anybody,” he told me, “but I’m not going to adjust my life or censor myself.” A few months ago, I met him at a coffee shop in Brooklyn. I showed up ten minutes early to get situated. Elliott was already there, sitting in the backyard under a tree, a little red notebook and a pen on the table beside him. People who know him have described him as a showman and a hustler — “a P. T. Barnum figure” of the literary world, as the novelist Claire Vaye Watkins once put it. But that was the Elliott who ran The Rumpus, the scrappy literary website he’d founded in 2009 and sold in 2017. The man I met spoke softly with a faint lisp, his legs crossed and hands clasped. He hadn’t talked to many reporters about the lawsuit. “Nobody’s coming my way,” he said sadly. He felt abandoned — by friends and agents, publishers and writers. “Not a single person in the literary world publicly defended me when it happened. And I launched a lot of people’s careers,” he told me. “Roxane Gay. Cheryl Strayed. I discovered all these people.” (Gay and Strayed, who sold Wild before writing for The Rumpus, disagreed. “The reverse is true,” Strayed told me. “It was through my ‘Dear Sugar’ column that people discovered his website.”) He mentioned his old managing editor Isaac Fitzgerald, whose memoir was getting rave reviews. After Elliott filed his complaint, Fitzgerald denounced the lawsuit on Twitter as “an outrageous act of violence.” Elliott shrugged. “Isaac was this guy who’d be homeless if it wasn’t for me, you know?”

If Me Too was Donegan’s moment, in many ways Elliott sees this as his. “I’m actually filing the lawsuit to stop lists like this from happening,” he said. He was no less convinced of the righteousness of his cause than Donegan had been of hers. “The list itself is inherently evil.”

Donegan was 27 when she created the list and six months into her tenure as an assistant editor at The New Republic. At the time, she and her colleagues were dealing with another man who, by their accounts, was perpetually crossing women’s boundaries.

It was a tense moment in the magazine’s storied history. The leadership had turned over repeatedly in the previous few years — at one point, more than half of the people on the masthead had resigned en masse. The new owner, Win McCormack, an heir to a midwestern banking fortune, had recently hired Hamilton Fish V, the wealthy scion of a notable New York political family, as publisher. Writers who covered the hire mentioned Fish’s progressive credentials, noting that he’d helped save The Nation, the country’s oldest liberal periodical, from insolvency. Absent from the coverage was the fact that his tenure at the Nation Institute was marred by allegations of misconduct. In one incident, he had allegedly grabbed a female colleague’s neck. (Fish denied doing this.) When women at TNR heard these stories, they warned new hires. One woman, a reporter-researcher just out of college, recalled another woman telling her to be careful around Fish. “We would make sure we were never in the elevator alone with him,” she told me. But it was impossible to avoid him entirely. One time, she said, she was sitting at a table in the middle of the office with a group of colleagues when Fish came up behind her, placed his hands on her shoulders, and held them there as he chatted with his employees. “I was deeply uncomfortable,” she recalled. “You just had to tolerate him,” another woman on staff told me. What else could they do? There was no union at the time. The human-resources manager had left more than a year earlier, and Fish had never hired a replacement. “That was the furnace the list was forged in, that conflict and messiness,” a former colleague said.

Fish was the fifth name on the list. All told, the spreadsheet identified men on every rung of the media ladder, from fledgling freelancer to editor-in-chief, at every major news outlet in the city along with a handful of publishing houses. As many commenters pointed out at the time, it could be seen as a modern incarnation of the whisper network — “the unofficial information channel that women use to warn each other about men whose sexual behavior falls on the spectrum from creepy to criminal,” as Jia Tolentino wrote in The New Yorker. When women turn to channels like these, it’s usually because they lack better options. In 1990, a group of women at Brown University wrote the names of alleged rapists on the walls of women’s bathrooms. The vice-president of university relations described them as “Magic Marker terrorists,” but at the time, Brown didn’t have a policy to investigate rape accusations.

Donegan was known by colleagues for her intense devotion to a particular vision of feminism. As she saw it, she’d been sold a lie as a middle-class kid growing up in Connecticut in the girl-power era. “The message issued by adults to little girls like me was relentlessly optimistic. ‘Girls can do anything now,’ we were told,” she wrote in an essay on her Substack, Not the Fun Kind. Then she entered the workforce and observed “a bunch of aging male bosses sleeping with their female assistants.” At some point, “it became impossible for me to ignore that sexism shaped the laws and institutions I lived under and within,” she wrote. In 2014, she helped start a feminist consciousness-raising group, a book club for friends who were “frustrated by the ‘defanged,’ Lean In feminism that was on the rise,” as a profile in Vice put it a few years ago. But Donegan wanted to do more than just read feminist texts. She wanted action.

On a Wednesday night, two weeks after the list circulated, a group of female TNR staffers including Donegan convened at a TGI Fridays to plan a strategy for getting rid of Fish. They debated speaking with a journalist, but in the end, they decided to write a letter to their editor, J. J. Gould, describing Fish’s alleged behavior; they also compiled a list of detailed allegations in a new anonymous spreadsheet. Donegan proposed including a mention of the “Shitty Media Men” list in the letter and advised her colleagues — some of whom had reservations about moving so quickly — to capitalize on the urgency of the moment. Gould received the letter the next day; by the following Friday, Fish had resigned. (“I resigned before a formal investigation was concluded,” Fish said in a statement. “Though I was later told I was cleared of wrongdoing, it’s clear that my presence made a number of female staffers uncomfortable. For that I am deeply sorry.”) He was one of the first on the list to lose his job but not the last. According to news reports, at least half a dozen resigned or were fired.

The list had supporters in the media, but the essayist Katie Roiphe, who had made her name disparaging the feminist outcry over date rape in the ’90s, was not one of them. “If we think of how we would feel about a secretly circulating, anonymously crowdsourced list of Muslims who might blow up planes, the strangeness of the document snaps into focus,” she wrote in a controversial Harper’s essay. As she was working on the essay, a fact-checker for Harper’s reached out to Donegan. Believing Roiphe intended to name her, Donegan outed herself as the list’s creator in an essay for New York Magazine’s the Cut. She acknowledged the document was “vulnerable to false accusations” and pointed to a disclaimer at the top that read, in part, “Take everything with a grain of salt.” Describing herself as “incredibly naïve,” she wrote that she “only wanted to create a place for women to share their stories of harassment and assault without being needlessly discredited or judged.” What happened next surprised her, she wrote. “I realized that I had created something that had grown rapidly beyond my control.” Leaders of Me Too, including Ashley Judd, lauded the piece as brave and eloquent, and Donegan was hailed as a feminist hero.

The same qualities that had made her a hero — her tenacity and boldness or, as some would see it, her zealousness and impetuousness — had also been causing problems for her at work. Some colleagues were put off by her pronouncements on Twitter (“Small, practical step to limit sex harassment: Don’t employ men”), by her confrontational manner, and by her relentless focus on her cause. “The ‘Shitty Media Men’ list was not just about identifying bad men but about remaking media in her image, which is a fine and noble pursuit,” one male colleague who has worked with Donegan told me. “But everything was part of this endless war that didn’t have much to do with making a magazine.”

A month after the list came out, Donegan was fired. In the Cut, she implied she had lost her job because of her role in creating it. Several sources at TNR pointed to other factors. One was her conflict with a critic named Jo Livingstone. Donegan edited Livingstone’s work. The two had been friends for years, stretching back to their days at n+1, where Donegan had volunteered in 2014. At one point they’d been romantically involved. Tensions arose between them in October, when they began arguing over ideological differences. On National Lesbian Day, Livingstone jokingly tweeted a link to their Venmo; Donegan, who is a lesbian, DM’d them to say they shouldn’t get to call themselves gay given that they had slept with men. “Don’t make me invisible just because you have internalized shame about being bi,” Donegan wrote. “Her arguments echoed the lesbian separatists,” Livingstone said. “That’s an intolerant wing within the queer discourse, and I really fell afoul of it.” Later, Donegan apologized in an email. “I’m an angry, messy person,” she wrote. “I’m trying to be better.”

Things came to a head on October 26, the day employees had planned to deliver the letter about Fish to Gould. In the newsroom, word spread that Gould already had a copy. In an attempt to figure out how he had gotten it, more than a dozen employees who had signed it gathered in a glass-walled conference room at the center of the office. Donegan charged Livingstone with leaking it. “She accused me of being a traitor and colluding with management,” Livingstone said. “It was a tremendously humiliating scene.” Livingstone had never shown Gould the letter. Later they learned several other colleagues had given him a heads-up about it. Livingstone felt they couldn’t work with Donegan anymore, so they asked Gould if they could work from home for the foreseeable future. Their request was granted. Soon after, Donegan was let go. “Moira’s termination was a process that included complaints from her manager about her work, that she was not productive, and it extended to her comportment toward other employees in the workplace,” one person with knowledge of the situation told me.

Donegan responded in a statement. “The weeks and months following the creation of the document were some of the most painful and frightening of my life,” she said. “It seemed inevitable that I would be fired, ostracized and worse. I was waiting for my life to fall apart and I was afraid. At my lowest, I lashed out at an old friend who was very important to me. I was not kind to Jo and the loss of their friendship is still something that I greatly regret. I am deeply sorry to Jo and I will always admire them.”

Livingstone said they still support the list. “It was kind of a stroke of genius,” they said. “And she’s very good at headlines.” At one point, they told management they would quit if Donegan was fired over it. “The list was ideologically flawed, practically flawed, humanly flawed,” Livingstone continued. “However, I do think there are things it achieved which nothing done sensibly could have. In the long term, that’s what really matters.”

Nearly a year after the list came out, Stephen Elliott published an essay in the right-leaning online magazine Quillette about how the anonymous rape accusations had “derailed” his life. This was not Elliott’s first choice of publication. Nine months earlier, he’d tried to place the essay in this magazine, where editors had first accepted his pitch but eventually rejected the draft; a similar thing happened at The Guardian. Elliott suggested at one point in our conversations that if New York hadn’t killed his piece, the lawsuit might not have been “necessary.”

In the Quillette piece, he wrote that festivals where he’d planned to promote his new book of essays rescinded their invitations in the months after the list appeared. His TV agent stopped calling. Elliott became depressed and contemplated suicide. He began using drugs again. A few months in, he sobered up and started going to meetings. He said he wanted to make amends. He contacted ex-girlfriends and other women he knew. He was sure he’d never raped anyone but worried he’d hurt people in other ways. After a while, he abandoned those efforts. He had come to the conclusion that it was “impossible to respond to an anonymous accusation.” It was a Kafkaesque scenario, he wrote in Quillette. “No one is truly innocent,” he wrote. “Even if you’re not guilty of the particular crime of which you stand accused, you’re likely to be guilty of something.” Regardless, “the trial is over before any defense can arrive.”

Publishing the essay did nothing to repair his image in the literary world. His old friends and colleagues — left-leaning writers and editors — greeted it with astonishment and scorn. But some readers responded positively to it, among them “people who believe they’ve been falsely accused,” Elliott said. He heard from a number of men who’d appeared on the list, and they began meeting in secret in New York. Around this time, he decided to file the lawsuit. Some of the other men found this heroic. (The former New Republic literary editor Leon Wieseltier called it a “splendid action.”) Miltenberg told me other men on the list contacted him but ultimately decided not to pursue a lawsuit. They had families to consider and worried getting involved would make things worse.

Besides, of all the men who had been named, Elliott felt he had the strongest case against Donegan. As defined by law, rape involves penetration of the vagina, anus, or mouth. Other men could claim they hadn’t had nonconsensual sex, but he could say he had a documented aversion to penetrating women’s bodies. What may be harder for him to argue, at least according to people who used to know him, is that the list destroyed his reputation in the literary world — a contention that is central to his lawsuit. Even if it’s true he has never raped anyone, he had behaved in ways that had already alienated many people in his community.

By the time he founded The Rumpus in 2009, Elliott was in his late 30s and had built up a cult following as a writer. Fans admired his ability to turn his emotional damage into art. Most of his work explored the psychological harm caused by his difficult childhood — by his father, who beat him, and by his time living in group homes and on the street. Elliott once wrote he became a writer because of “an urge to release a scream” that was stuck in his throat.

At The Rumpus, there was no money to pay writers or most of the editors, but Elliott was good at persuading people to work for free. He had a sharp eye for talent, and “he had this way of creating a scene you wanted to be a part of,” said writer and editor Sari Botton, recalling a packed reading in the early days of The Rumpus. “He’s talented. And he’s magnetic.” He was also, she added, “definitely a guy with boundary issues.”

Although Elliott identifies as submissive, women found him to be pushy. He could be physical in a way that made some women uncomfortable. Botton, who wrote a column for The Rumpus, recalled him draping himself around her at a reading at a bookstore. “He put his head in my lap and started massaging my legs in public, and I was like, Oh, God, and I just froze.” In her memoir, Hysterical, Elissa Bassist wrote about volunteering for an online magazine whose editor would casually put his hand in her back pocket at events and beg her to take naps with him. She doesn’t name Elliott, but when I reached out to her, she said it was him. “I was always trying to figure out ways to say I was busy, I was sick, because I was so afraid of hurting his delicate feelings,” she said. Another woman, a writer in the kink scene in San Francisco who asked to be identified as R.D., recalled showing up at a writing workshop Elliott was leading in a dungeon. When she walked into the room, she said, Elliott “stopped the class and dove at me and threw his face into my tits and started moaning.”

Elliott told me he had “clearly misread” his relationship with Botton. “I thought we were close friends,” he said. Asked if he had stopped a class and pressed his face into a woman’s breasts? “Inconceivable,” he said. As for Bassist, he called her a liar. “I never begged her to take a nap with me,” he added. Yet someone else who worked at The Rumpus told me this behavior was “ubiquitous.” “I also received those invitations,” she said.

One incident likely affected his public image more than any other. In the fall of 2009, the novelist Claire Vaye Watkins was in the final year of her M.F.A. program at Ohio State when Elliott came to give a reading. Watkins’s professor told the cohort Elliott needed a place to crash, and Watkins, who’d never met him, offered to let him stay at her apartment. When they got back to her apartment after the reading, Elliott pressed, repeatedly, to sleep in her bed rather than on the air mattress she’d inflated for him. He insisted it would be like sleeping with “your gay friend” and gave up only after she told him she was seeing someone. Later, Watkins saw that Elliott had written about the encounter in the newsletter The Daily Rumpus in a way she felt revealed a failure to take women seriously as artists.

In 2015, she described the experience at a gathering hosted by Tin House, the literary magazine. In her talk, a sweeping assessment of sexism in the literary world, she cited Rebecca Solnit’s concept of a continuum of sexual violence, drawing a connection between how Elliott treated her and a culture that facilitates rape. “Stephen Elliott did not rape me, did not attempt to rape me,” she said. “I am not anywhere close to implying that he did. I am saying a sexist negation, a refusal to acknowledge a female writer as a writer, as a peer, as a person, is of a piece with sexual entitlement.”

After she spoke, a handful of women in the audience told her they had had similar encounters with Elliott. Rob Spillman, the editor of Tin House, encouraged Watkins to publish the talk as an essay. It became the most-viewed web piece in Tin House history and undoubtedly shaped the literary community’s view of Elliott. “It started a reckoning,” Spillman told me. After the piece came out, he said, “he didn’t have a lot of margin for error.” Elliott doesn’t disagree. “I was seen as a bad guy, and people whom I’d been friendly with were not friendly anymore,” he said. (He added he’d interviewed Watkins after he spent the night at her place and published the interview, “so this idea that I didn’t think of her as a person is off.”)

If Elliott hopes the lawsuit will salvage his reputation or restore his standing in the literary world, he may be disappointed. His literary agent dropped him after the suit, not the list. Lawyers who specialize in defamation speak of something called “the Streisand effect.” In 2003, Barbra Streisand filed a $50 million lawsuit against a photographer who had taken an aerial photo of her Malibu mansion and a website that had published it. The image had been downloaded only six times prior to the lawsuit, twice by her attorneys, but in the month after her case was written about in the press, 420,000 people visited the website. The parallel to Elliott’s case is obvious. It seems as if each time he has talked about the lawsuit, more women have come forward and shared stories about how they felt he mistreated them and more readers have learned about those incidents. Elliott says this doesn’t bother him. “I was falsely accused of rape, and when I said I was falsely accused of rape, your response was ‘Well, you made me uncomfortable at this conference,’” he said. “Who cares?”

Strayed, who has been friends with Elliott for a decade and was beloved by readers for the advice she gave in her “Dear Sugar” column for The Rumpus, tried to talk him out of suing. She knew he liked to cross boundaries when it came to personal space — he had tried to sit in her lap at a writers’ conference and pleaded with her to let him sleep in her bed. (Elliott says he never asked to get into bed with Strayed.) But she believed him when he said he’d never raped anyone. “I think Stephen needed a real corrective, and he had things to learn, and that he’s been falsely accused of rape,” she said. “That’s why I could say, ‘I love you, Stephen, and I know you didn’t do the worst thing you’ve been accused of here, but you’ve made a lot of women feel this way, which is why you’re on the list.’ ”

She offered Elliott some advice. “Conduct yourself with grace in the court of life,” she recalled telling him. “Do it and be it and people will see it — prove it wrong in your life rather than the court of law.” She wasn’t surprised that he didn’t take her suggestion. “He’s intellectually principled,” she said.

Elliott told me several times he was filing the lawsuit for moral reasons. Noting his history as an advocate for prison reform, he said, “The presumption of innocence means guilty people are gonna get away with stuff. That’s more important than capturing every guilty person.” He suggested he could in theory support a system for anonymously reporting sexual misconduct but that whoever oversaw it would need to keep the identity of the accused private as well. Early on, much of the Twitter outrage directed at his lawsuit centered on his attempt to unmask the anonymous women who had added his entry to the list. “But here’s the thing,” he told me. “I don’t care who wrote my accusation.” Whoever did, he said, “is just a crazy person.” Donegan, on the other hand, was a bully and a liar. He didn’t believe she’d intended the list to serve as a private forum, as she had claimed in the Cut. “Pure b.s. from start to finish,” Elliott said. He thought she’d always wanted the list to go public and had used it to “remove her enemies from power.” Over the summer, in an email to Spillman, the Tin House editor, who had tweeted in support of a GoFundMe drive for Donegan’s legal defense, Elliott wrote, “Moira has to be stopped.”

Elliott’s lawyer, Miltenberg, works in a midtown office decorated with family photos, framed newspaper clippings, and Civil War memorabilia. Figures of both Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant stand on a shelf above his desk. He described himself to me as a history buff. According to his reading of history, the culture of anonymous accusations that has flourished in the age of social media has a troubling precedent. “Looking back at the Red Scare and McCarthyism, it was enough for someone to be accused of having read a book on Trotsky 30 years ago for them to be blackballed within an industry,” he said. “The mere accusation was enough to damage someone’s career and future. That’s what’s happening now, to a degree.” He said he gets several calls a week from people who say they have been falsely accused of sexual harassment on the internet. “The fact that this relatively new venue of social media is a place where you can do that doesn’t mean it should stay like that,” he said.

There is, however, another historical view one can take of Elliott’s case. “Our protections for anonymous speech actually predate the First Amendment,” said Aaron Mackey, a lawyer for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for user privacy and free expression. “We recognize the historic tradition in our country of protecting anonymous speakers because we think there’s real value in giving people the space to advocate for social and political change.” This is especially true when the speaker has good reason to believe they may face serious consequences for telling the truth, as women who report rape often have.

In defamation cases concerning anonymous speech, courts must balance these opposing concerns — fairness for the accused and protection for a vulnerable accuser. As the law exists today, the right to anonymous speech is not absolute. A judge will sometimes allow a plaintiff to learn the identity of his accuser, but first the plaintiff has to convince the judge he has a plausible case. Elliott has managed to do that, but he has run into another obstacle: Donegan deleted most of the emails and texts she sent while the spreadsheet was online, and Google does not store deleted data indefinitely. Without that information, it may be impossible for Elliott to find out who added his name to the list or who actually accused him of rape. Elliott may not care about that personally, but if he can’t uncover an accuser’s identity, it will be difficult for him to disprove the claims. He wouldn’t be able to say, just to take one hypothetical example, he was playing poker with his friends on the night of the alleged crime. If anything is Kafkaesque about his situation, this is it.

His lawsuit suggests he might pursue an alternative strategy if the case goes to trial. It argues that Donegan and the list’s other contributors either knew or should have known he could not have committed rape because of his extensively documented sexual preferences. In its filings, Donegan’s team scoffed at this notion. “As a factual matter, this ‘too submissive to rape’ defense is obviously absurd,” Kaplan wrote. Besides, it did not plausibly follow, Kaplan argued, that whoever published or edited Elliott’s entry agreed that “BDSM submissives cannot engage in rape” and decided to accuse him anyway.

Kaplan has a track record of winning difficult cases. (She declined to comment on this case. Given the “pendency” of the lawsuit, “it would not be appropriate,” she wrote.) Back in 2013, she successfully argued before the Supreme Court that married same-sex couples deserved federal recognition and protection. In October, she deposed former president Donald Trump in another kind of defamation case that has become common in the wake of Me Too. Her client, the writer E. Jean Carroll, who accused Trump of rape in a 2019 New York Magazine article and a memoir published by St. Martin’s Press, is now suing him for calling her a liar.

Yet her defense of Donegan hasn’t gone as smoothly as she predicted. So far, she and her team have twice tried and failed to get the case dismissed. One of their attempts invoked something called Section 230, a part of the Communications Decency Act. Passed in the mid-’90s, Section 230 shields websites and social-media platforms from bearing responsibility for what their users post. Without it, the internet as we know it could not exist. It is because of Section 230 that Yelp, for instance, cannot be sued for defamatory statements each time a reviewer rails about bad restaurant service (though reviewers can be, and have been, held liable). In the past, Section 230 has also been used to protect publishers of online forums where men harass and menace women. Jeff Kosseff, a cyber-security law professor who has written books about Section 230 and anonymous speech in America, pointed to a website called TheDirty.com. Users of the site would submit gossip to the site’s owner, the blogger and internet personality Nik Richie, who would select submissions and post them. The gossip, which often concerned young women, could be mean-spirited and misogynistic. But all of the women who sued Richie for defamation failed because Section 230 protected him. “The constitutional right to anonymous speech came from protecting the NAACP, but it also protected the Ku Klux Klan,” Kosseff noted. “Is anonymity good or bad? It depends who’s using it.”

Donegan’s team argued she should qualify for immunity under Section 230 because she merely provided a forum for the list’s contributors and exercised no influence or control over the content, which means she wouldn’t be held responsible for whatever they wrote. The judge dismissed this effort partly because it wasn’t clear, based on the depositions and the evidence available so far, what role Donegan had played in shaping the list. What if she had in some way encouraged a contributor to add false accusations to Elliott’s entry? In an affidavit, Donegan said she had “no recollection” of encouraging anyone to add information about Elliott, but this wasn’t enough to convince the judge that she hadn’t.

Now the lawsuit seems headed toward settlement or trial. Discovery is scheduled through April of next year with a status conference set for next November. If a trial happens after that, the jury’s determination would likely hinge in part on how they see the wisdom of what Donegan did and the picture that emerges of Elliott’s character. The lawyer who would cross-examine Elliott is a formidable former prosecutor who interrogated terrorists for the Justice Department, and he would surely do his best to argue Elliott’s history with women shows his reputation was damaged before the list was created. That could hurt Elliott’s chances of collecting a payout even if Elliott convinces a jury he never raped anyone. “What would be somewhat ironic,” Tuerkheimer, the Northwestern law professor, said, “is a finding that this was defamatory but the damages are nominal because he already had such a bad reputation.”

Some of Elliott’s peers in the literary world have speculated that he is filing the lawsuit in order to attract a new audience. “I think he would probably rather have had a different show,” one former collaborator said, “but this was the show available to him.” I thought of something Elliott had told me about attention. “Attention — I’m convinced of this — attention is currency,” he said. “If there’s a lot of it, people want that. It’s like money to them. It will not lie there unclaimed.” This phenomenon, as he saw it, all but proved he hadn’t raped anyone. “If there’s an anonymous accusation of multiple rapes, there might be some other people who don’t come forward, but someone will come forward,” he said. “Attention has this magnetic pull.”

It’s true that Donegan has attempted to profit from the attention the list brought her. In 2018, she sold a book proposal off the list at auction to Scribner. Still, Elliott’s point about the irresistible allure of attention elides an important truth. When women come forward to make accusations, they face harassment, threats, and other consequences, which is why, as Elliott himself acknowledged in our conversation, rape is vastly underreported. By filing this lawsuit, as many defense attorneys have observed, Elliott may make the problem worse. Even if he doesn’t win, he has forced Donegan to endure years of litigation. This already seems to have had a chilling effect. One woman who knew Elliott told me she couldn’t allow me to share her story because he’d shown himself to be “legally sadistic.” Although it’s true that the list, as Elliott often pointed out to me, inflicted punishment before the public could consider all the facts, the same could be said about his lawsuit.