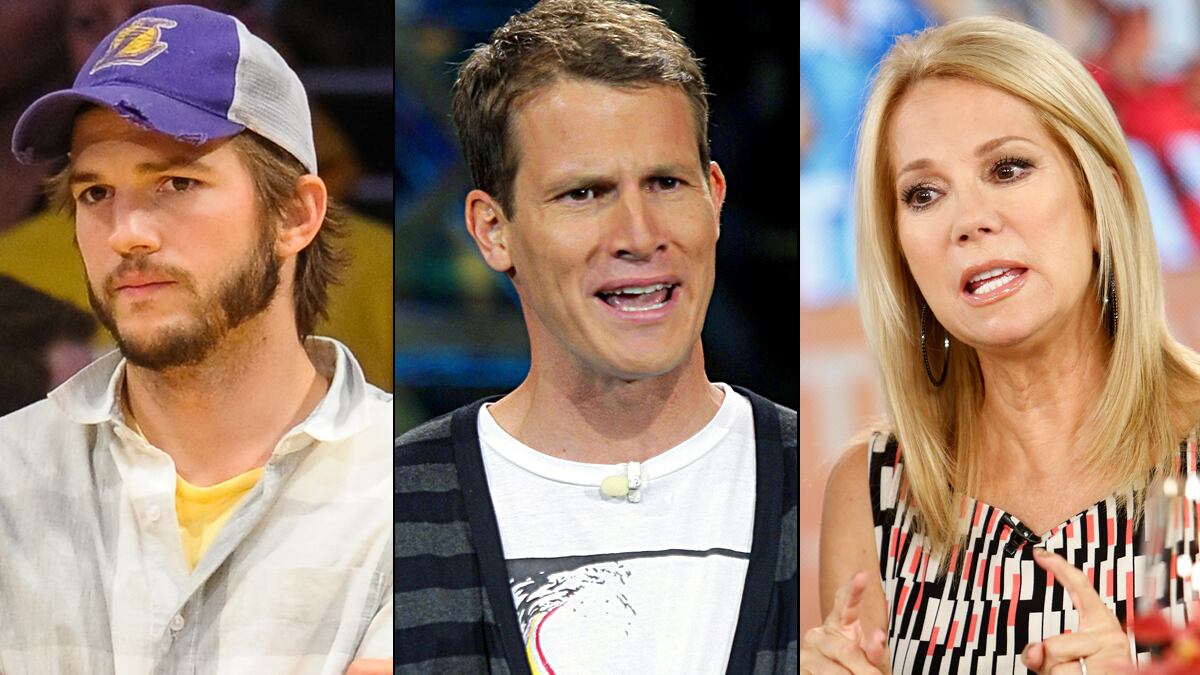

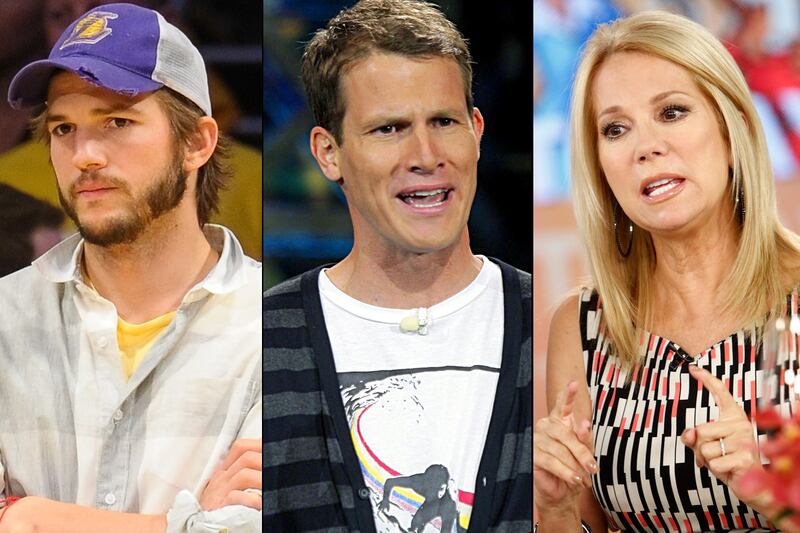

Daniel Tosh was wrong, of course, to say that it would be “funny” if a particular woman in his audience got gang-raped. So he “apologized”.

The problem is, his apology was delivered through his Twitter account. Apologizing via Twitter is like marking your anniversary by having your secretary send a JPEG of a rose to your wife. It’s superficial and smacks of a lack of thought and effort, and Tosh’s non-apology is a prime example of why this ridiculous practice needs to end.

In fact, there’s no cheaper, more depressing sign of how quickly we’re riding toward a future where even the most meaningful sentiments get stripped down to tiny strings of characters followed by snarky hashtags.

Tosh, of course, is merely the latest in a long line of celebrity Twit-pologists. To take just a few recent examples, the head football coach at Vanderbilt University apologized via Twitter last month for sexist comments he made. In May, Kathie Lee Gifford sent a Twitter apology to Martin Short after asking him repeatedly, on-air, about how he had stayed happily married for so long—except that his wife died in 2010 (to be fair, she also issued an on-air apology). And last November, Jimmy Fallon tweeted an apology to Michele Bachmann after his talk show’s house band, The Roots, played the song "Lyin' Ass Bitch” as Bachmann walked onstage for an interview.

I can hear the skeptics. “Who cares?” they ask. “Most apologies are insincere anyway.”

Well, maybe. But to my mind, even the classic non-apology apology (the one that always includes some variant of “I’m sorry if anyone was offended”) is better than the ultra-abbreviated Twitter version.

A wild hypothetical: Let’s say I hate puppies, and my next article is about how much I like punching them in their little puppy faces. The article is met with a torrent of pro-puppy criticism, and I feel obliged to issue an apology. If I sit down and write a paragraph-long apology—even if it’s just 150 words—I’m being forced to confront the anger being leveled at me, to at least approximate something like empathy toward puppies and puppy-lovers. This may not sway me toward an understanding of my wrongdoing or make the apology sincere or turn me into a less awful person, but at least I’m taking a moment to engage with the feelings of my critics.

If, on the other hand, I send out a Tweet which reads “o hi guyz srry bout puppy column sum of my best friends r puppies #puppiesaregreat”—sandwiched between one tweet about what I ate for lunch and another about how I thought Moonrise Kingdom was somewhat disappointing—have I been inconvenienced at all? Have I even tried to understand the pro-puppy viewpoint? Will I even remember that I tweeted it tomorrow?

The apology is one of those social compacts that may seem awkward but keep human civilization going: You hurt my feelings, I tell you that you did, you give me a sincere-sounding apology, I accept it, and we both move on.

Twitter apologies cast these conventions to the wind. How can you squeeze any real (or even real-sounding) sentiment into 140 characters? If you genuinely feel the need to apologize for something, and you have the resources to do it in any manner you wish, why not at least release a statement? Write a blog post? Anything but the deadening short bursts of Twitter text.

Sure, in theory, it’s possible to issue a sincere apology via Twitter. But obviously Twitter is, by definition, not the place for substantive, nuanced writing—both of which should appear in a good apology. To the contrary, writing an apology on Twitter is a pretty good indication that you aren’t that concerned about your actions. Tosh is a prime example of why this matters, because he was facing an uphill credibility battle anyway. (He recently encouraged his viewers to upload videos of themselves touching fat women’s bellies.)

Not every celebrity has taken the lazy route in the wake of a blunder. Some have gone about it the right way. After tweeting out homophobic comments about a David Beckham Super Bowl commercial, CNN commentator Roland Martin issued an on-air apology: "If you're gay or straight, your voice matters,” he assured his audience. It sounded heartfelt and returned him to the good graces of GLAAD, the gay-rights group that had originally called for his firing. (I’ll also admit that it was one of those rare apologies that actually would have fit in a tweet.)

And Ashton Kutcher didn’t just apologize for tweeting outrage over Joe Paterno’s firing—he subsequently turned control of his Twitter feed over to his publicity team, a sign that he genuinely understood that there needed to be a buffer between his fingers and that enticing “Tweet” button.

In other words, this is how apologies should happen—with some level of genuine-seeming self-flagellation.

I recognize that complaints like this can quickly devolve into standard-issue cultural panic over technology. But I’m no Luddite—I came of age during the glory days of AOL Instant Messenger and have defended email from sentimentalists who insist that the only way to write a “real” letter is to do so on paper. I’ve argued against technophobic hysteria over sexting and, like everyone else my age, it’s rare that a day goes by in which I don’t send or receive multiple text message. And like basically everyone else, I’m on Twitter.

The bottom line is that we lose something important every time we cede a form of communication to our twitchiest impulses. Not everything needs to be sloppy and haphazard and done in a hurry.

Now please tweet this column far and wide.